In spring of 2020, Cornell became the first Ivy League institution and the sixth university in the world to receive the highest possible rating for its sustainability efforts—STARS Platinum. The STARS ratings measure campus sustainability across a range of dimensions, from the food Cornell serves to the energy it produces, and from the courses it offers to the ways the university engages with the public to share sustainability and climate education.

Cornell earned a perfect score from STARS in the engagement category—an acknowledgement of the university’s success in making sustainability part of campus culture and ensuring that all students engage with sustainability learning outcomes before they graduate.

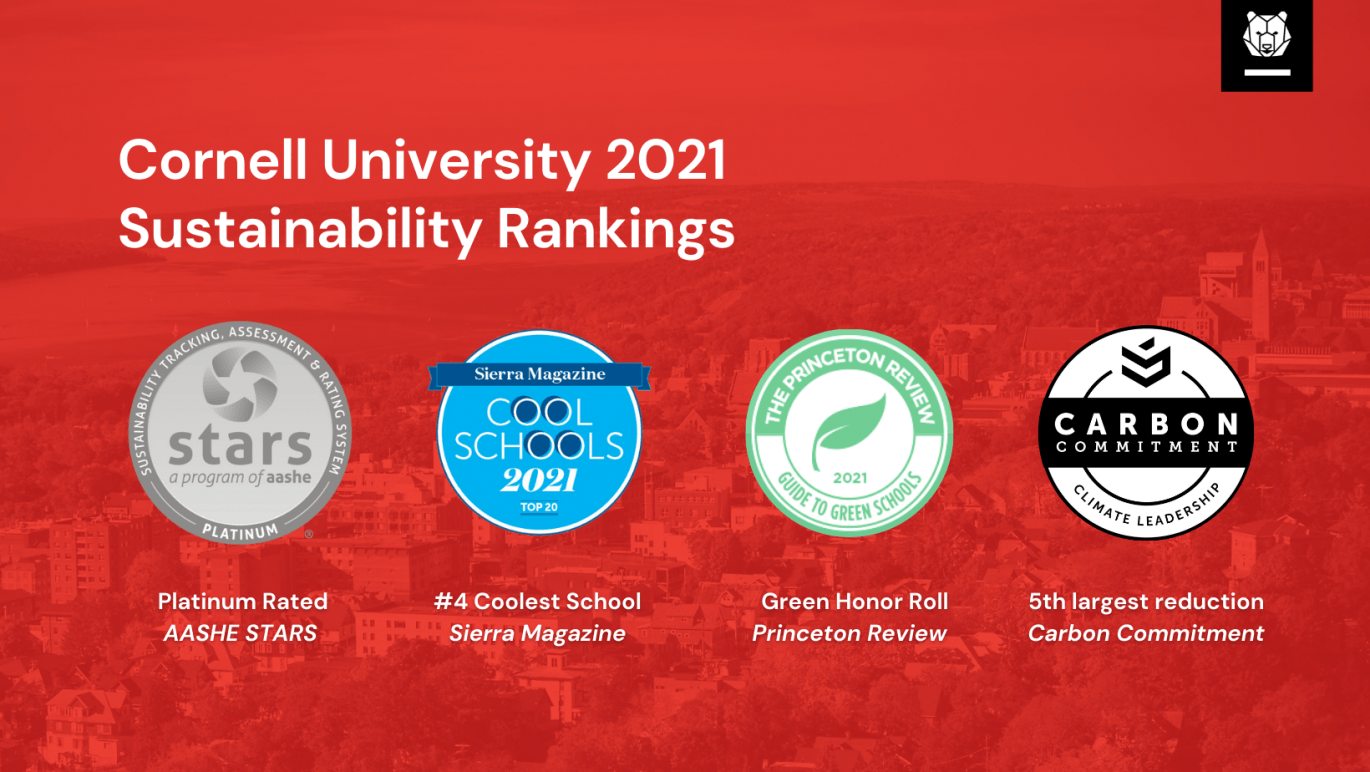

Cornell received numerous other recognitions for its sustainability efforts in 2021:

- Fourth Coolest School, and the only Ivy in the Sierra Club Cool Schools top 20 schools

- Eighth Green College, and the only Ivy in The Princeton Review Green College Honor Roll

- Three Marks of Distinction, and the top Ivy for overall carbon reduction according to Second Nature

This success can be attributed to many factors. They include the willingness of university leadership to set bold climate action goals, the expertise of Cornell staff and faculty who figure out how to achieve those goals, and the commitment of Cornell students to advocate for change.

Students are at the heart of Cornell’s sustainability story, and they were the spark behind the university’s first formal climate commitment in 2001. Here we share the story behind this commitment, from the perspective of a few of the students (now alumni) and staff (many of whom are also Cornell alumni) who were involved in negotiating the commitment.

We also share the story of one alumna, Abigail (Abby) Krich Starr ’04, MEng ’06, who served on Cornell’s first Kyoto Task Team—the committee charged with implementation. Abby’s experience working to implement carbon reductions at Cornell inspired her lifelong commitment to climate action and her successful career at the forefront of the renewable energy field.

Students at the heart of the story

Abby entered Cornell in the fall of 1999, when nations around the world were debating adoption of the Kyoto Protocol—a set of voluntary commitments to limit greenhouse gas emissions. When the U.S. failed to commit to the Protocol, which called for a 7% reduction in the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2008–2012, a group of Cornell students calling themselves Kyoto Now! (KN) asked the university to commit to this same level of reductions.

According to Lindsey Saunders ’04, Kyoto Now! was founded by several members of the Cornell Greens, a group of students interested in sustainability who had attended COP6 in November 2000 in the Hague, Netherlands. The students’ experience at the conference convinced them that the U.S. government was not taking responsibility for our country’s role as the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gases. The students believed that research institutions like Cornell could step in to fill the leadership void.

When the students returned to campus, they began working on a plan to get Cornell administrators to commit the university to its own version of the Kyoto Protocol. They named their group Kyoto Now! (KN). “Our name was distinctive and we made hundreds of buttons that raised dozens of questions per day,” Lindsey says. “We asked, ‘If not us, who? If not now, when?’”

“Cornell was uniquely positioned to make new investments in developing and implementing green technologies,” Lindsey says. “Cornell’s leadership could demonstrate the feasibility of reducing carbon emissions.”

If not now, when?

“The students caught a moment in time,” says Lanny Joyce ’81, retired director of Utilities and Energy Management for the university. “They asked the question, ‘Can Cornell adopt a Kyoto pledge, as if we were the U.S.?’”

In early 2001, KN members met with Cornell faculty, facilities managers, and administrators to discuss their request, but were unable to secure a commitment. The students decided to hold a press conference and stage a sit-in at Day Hall. Six core members of KN were joined by hundreds of students throughout the next week (April 12-18, 2001), during which they maintained a 24-hour presence outside Day Hall. They collected nearly 5,000 student signatures in support of their effort.

“Students showed their overwhelming support for Cornell to take action on the pressing topic of our time,” Lindsey says, adding, “This support helped in our ongoing negotiations with the administrators. We pushed for Cornell to make a commitment that would signal real action.”

Susan Murphy ’73, PhD ’94, then vice president for Student and Academic Services, helped to negotiate with the protestors, who subsequently agreed to leave Day Hall when the building closed for the day and not to obstruct access to the building during business hours. Susan recalls driving to campus on Saturday morning, “to wake up the students sleeping in their tents before the Saturday a.m. campus tour, because I was sure they would sleep in (and indeed, they were all asleep). Everyone was very cooperative,” she says.

An educated yes

Harold (Hal) D. Craft ’60, PhD ’70, then vice president for Administration and chief financial officer of Cornell, had to move quickly to respond to the students. Hal had been deeply involved with energy projects at the university for about twenty years, in his prior position as vice president for Facilities and Campus Services. “I was one of the major negotiators for the senior administration,” Hal says, “since the issue in question fell squarely within my responsibilities.” He reached out to Lanny Joyce, to see if the reductions the students were asking for were possible.

Lanny managed supply-side energy planning for the university, as well as energy management of the physical plant—its buildings and associated infrastructure. At the time, Lanny had recently completed the Lake Source Cooling project, an innovative effort to cool campus by relying on a naturally renewable source of chill, namely the deep water of Cayuga Lake. He believed that the university had a tremendous opportunity to reduce its energy use through conservation measures, so he was receptive to investigating the student’s request.

“We were all so illiterate,” Lanny recalls, explaining that no one had ever done a greenhouse gas inventory for Cornell. He pulled together his team of two engineers and they completed the inventory within a matter of hours. “First, we had to figure out how much carbon dioxide comes from burning a ton of coal, we had to inventory all of our energy use, and then we had to try to project the university’s growth (and associated impacts on emissions) through the 2008–2012 deadline,” he says, adding, “We looked back at the past 11 years and made an educated guess.”

Lanny explains that, at that time, Cornell had about 150 buildings of varying ages and varying degrees of efficiency. Just as regular preventative maintenance on a car can greatly improve the efficiency of the vehicle over time, Lanny thought that Cornell could realize significant energy and cost savings by implementing routine preventative maintenance on its buildings. According to his team’s estimates, Cornell could make Kyoto-equivalent reductions in its emissions by the deadline—if it adopted an aggressive energy conservation program and transitioned away from burning coal. He told Hal that the answer to the students’ question was yes.

Commitment with no crystal ball

Hal says that, looking back on the situation today, his main sticking point was “the absolute commitment to a goal when I had no concrete idea either about the potential future university growth (which has been substantial), or what further mitigation steps might be taken or the university’s tolerance for them.” He adds that, “I recall being in complete agreement with the student activists regarding energy conservation and reduction.”

“The goals of the Kyoto Now! protest were hard to argue against,” Susan agrees. “Often you are asked to make decisions with incomplete data or knowledge. I think the student energy on this topic brought the issue to the forefront and led the administration to take a stand,” she says.

Hal explains prior to the Kyoto Now! protest, much of the work to reduce energy consumption on campus had been done behind the scenes. “The work up to that point had been cost-effective and relatively invisible to the campus community,” he says. “I believe that student activism was important and perhaps critical, to bringing to the fore important stuff that was already underway, increasing its visibility and its support throughout the community.”

Lindsey says that KN’s winning strategy was to make a global challenge a local one. “We targeted our own institution to take action. We researched and learned, met with people all over campus, and had an excellent branding campaign: Kyoto Now!,” she says. “We demonstrated that the administration had broad support for committing to be the leader we all knew Cornell could be.”

Doug Krisch ’99, MRP ’03, one of the core group of KN student organizers, says that the students kept negotiating with administrators until they reached an agreement they felt had “teeth”: “We continued until we felt they committed to the standards of the Kyoto Protocol,” Doug says.

“Cornell was the first major nongovernmental institution to voluntarily commit to the Kyoto Protocol standards for greenhouse gas emissions reduction,” says Frankie Abralind ’01, another core member of KN. “This was an incredibly significant event, and it came via a student-led campaign,” he says.

On April 17, 2001, Hal issued a statement affirming Cornell’s commitment to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gasses. Here is an excerpt:

“Let there be no mistake about it: the attainment of a reduction by 2008 of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions attributable to campus activities to levels 7 percent less than what they were in 1990 will not only be very difficult, it may be unable to be reached despite our best efforts. Nonetheless, the standards established by the Kyoto Protocol serve as a standard for communities as well as nations to emulate. With this in mind, I hereby commit Cornell University to do everything within its ability, consistent with the university’s obligations for teaching, research, service and extension, to implement the Kyoto Protocol standards and to issue a regular report on our progress.”

Realities of implementing change

Hal’s statement concluded with a promise to form a committee comprised of faculty, staff, and students that would be charged with implementing the reductions. In hindsight, Hal believes that the students who served on this committee greatly benefited from the experience of working through “the realities of trying to implement a major physical program or societal change.” Abby couldn’t agree more.

Abby recalls bringing gallons of hot chocolate to the members of Kyoto Now! who were camped outside. “I wasn’t one of the students camped out, but I marched and sang with them in the street, and raised my hand to work with the implementation team to figure out how Cornell could actually meet its commitment once Vice President Craft made it,” she says. “It’s what led me to the career I am in, working in renewable energy and trying to shift the wholesale electricity markets system to enable large-scale integration of clean energy.”

Abby says that the mechanics of how to achieve Cornell’s climate commitment were what attracted her to support KN, and to raise her hand to serve as one of two students on the Kyoto Task Team. Lanny Joyce spearheaded the new team, which consisted of a few university engineers, faculty members, and student volunteers.

The task team met bi-weekly, and Lanny says that they had great discussions. The meetings were very democratic and everyone was treated equally, he explains. He encouraged the students to make suggestions and ask questions. “Any idea was fair game, as long as it made single bottom-line sense,” Lanny says. Lanny had a small budget—a few hundred thousand dollars—but what he describes as “a huge task to accomplish.”

At first, the team focused on projects which did not spend money, but instead saved the university money. They were able to realize significant cost and energy savings through preventative maintenance on poorly performing buildings. Within a few years, they began upgrading the control systems in these buildings to increase energy efficiency. “All of these early projects yielded a 5- to 10-year payback on investment,” Lanny reports.

Lanny feels that his work with the Kyoto Task Team was a highlight of his career. “The students on the team were passionate, but they were willing to learn and understand the math, physics, and science behind energy production and use,” he says. Lanny especially loved working with Abby, whom he credits with bringing the first solar installation to campus. “Solar wouldn’t have happened if she hadn’t been so reasonable, so compromising, and so knowledgeable,” he says, adding, “and now we have 10MW solar installations!”

Room with a view of solar panels

Abby served on the Kyoto Task Team from fall 2001 through her graduation in May 2004. She recalls pressing for more supply-side change. “We were very focused on reducing energy usage and promoting efficiency,” Abby says. “I remember wanting the university to do both—to conserve and to use clean energy.” She worked with other students, including a few MBA candidates, to craft proposals to install solar panels and build a wind farm to help power campus, but these proposals were rejected.

Kyoto Now! faculty advisor, Professor Zelman Warhaft, received a donation of 90 used solar panels from Richard Aubrecht ’66, MEng ’68, PhD ’70, former vice president of Moog Corporation and trustee emeritus of Cornell. Lanny and Abby tested the panels and verified that they were still productive, and Abby stepped up her efforts to get these panels installed at Cornell.

She recalls meeting with Lanny and then with Hal Craft to try to “break the log jam” for a solar installation on campus. At one meeting at Hal’s office in Day Hall, Abby gazed out the window at the building’s flat roof. “I asked him if we could put the panels there,” she recalls. Hal replied that they would need to confirm that the building was structurally sound enough to accommodate the solar installation. “I asked him, ‘What if the building is structurally sound, and what if we raised the money to fund the installation?’ And he said ok.” This conversation happened in the spring of Abby’s senior year, shortly before she graduated.

Structural analysis showed that the roof of Day Hall could accommodate the panels. In honor of her graduation, Abby and her family created the Krich Family Solar Fund to support a portion of the cost of installing solar panels on campus. About 30 other alumni also contributed to the fund. With the panels and seed funding in hand, Abby secured the administration’s approval to proceed. She recalls that Rob Garrity ’05, a Cornellian who worked for a local solar company, assisted with the design, and the Electrician’s Union’s apprentice class donated their time to help with the installation. “It was a real group effort to get this job done,” Abby says.

Abby hopes that the Day Hall solar installation helped to shift attitudes toward solar energy at Cornell. “I always like to think that having the administrators sitting there looking out at the panels from their offices influenced their thought processes. I never heard again that they were ugly. From then on,” she says, “Cornell really made a commitment to sustainability.”

Finding her own way

In addition to her work on the task team, Abby also wrote a column on energy and the environment for the Cornell Daily Sun. One of her columns focused on objections to a proposed offshore wind farm near Cape Cod that had been raised by surrounding property owners. Randall Swisher, then executive director of the American Wind Energy Association, read Abby’s column and invited her to a conference to learn more about wind energy. There, Abby attended a talk by Trudy Forsyth of the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL). After the talk, Abby introduced herself and Trudy asked for a copy of her resume.

Next thing she knew, during senior year finals week, Abby was offered a position at NREL’s National Wind Technology Center near Boulder, Colorado. “I showed up two weeks later with no discussion about what I would do,” she recalls. “I had a lot of freedom, so I bounced around and settled in with the grid integration group,” she says. This group was working on how to integrate variable resources like wind and solar into the electric grid—a challenge which deeply interested Abby.

After six months at NREL, Abby moved to a job with Northern Power Systems in Vermont, where she worked on the nuts and bolts of designing mid-sized solar systems. Her experiences working with renewables made her realize that she wanted to deepen her understanding of how electrical grids operate, and of how to optimize integration of renewables on a larger scale. In 2005, Abby returned to Cornell to pursue a masters degree in electrical engineering.

Abby credits a one-credit class on electricity markets with changing her career trajectory. The class brought together engineering with economics to explain how market-based energy systems work. At that time, electricity markets in the Northeast region of the country had recently been deregulated—meaning utilities no longer owned and operated the power plants. This change opened the door to renewable producers to sell their energy in the market.

“This class was at the intersection of engineering (i.e., the physical constraints of the grid itself) and economics (i.e., optimizing financial interests),” Abby says. Students engaged in a simulation in which they played power plant operators in a market and were able to earn real money. “I earned enough to buy myself a new pair of ski boots!” she says. “My interest is to get more clean energy on to the grid. In this class I learned that these are the rules and this is the game that clean energy has to play to succeed.”

Over the past 15 years, Abby has helped many clean energy producers compete in the marketplace and realize a fair return on their investment. “The market is created by a totally behind-the-scenes community where the rules change all the time,” she explains. “I want to ensure that the rules enable the transition to clean energy, rather than favoring incumbent fossil fuel generation.”

Abby says her persistence and dedication to do what’s right have paid off. “Ever since my days as an undergrad at Cornell, I try to do my homework. I know what I’m asking for and what it means,” she says. “I don’t know how many times I asked to put solar panels on campus. When they said no, I just kept asking. This was the best possible training for what I do now!”

Speaking to current Cornell students, Abby advises them to seek out and create their own paths. “Job listings are not the extent of what you can do,” she says. “Go to conferences, talk to people, create projects on campus, ask for what you want, and make your own opportunities.”

Lifelong rewards

Abby’s and Cornell’s sustainability success stories are set against a backdrop of sobering scientific realities—including record high greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, and a 2021 UN analysis indicating that the global commitments made under the Paris Agreement will fail to keep global warming under 1.5C in this century.

Bruce Monger, director of undergraduate studies for Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, says that he always shares Abby’s story with his students, as an example of what they can accomplish. Bruce teaches Introductory Oceanography—among the largest and most popular courses at Cornell.

“Abby’s story shows them that they can have a real, lasting impact on making a better world,” Bruce says. “I tell them, ‘Think of the lifelong rewards and warm emotional glow you will feel if you act today. This is how you want to feel as you grow old and grey.’”

“The Kyoto Now! students were passionate about a problem that will plague their generation even more than mine, so frankly, I applaud their push,” says Susan Murphy, adding, “I think it helped move an otherwise slower-moving institution toward action. And, as Abby demonstrated, the students were not just active politically in this area, they also were active intellectually and through their work. When that happens, they are real partners.”

Lindsey Saunders is proud of Cornell for the investments it has made in climate action in the 20 years since she took part in the 2001 Kyoto Now! protest. “The progress made over the years has been lauded and is laudable,” she says. “But it is important to remember that it needed a solid, public nudge to make that commitment.”

“If we want to contribute to the trajectory of our schools, our communities, our families, our cities, we must often stand up and stand out,” agrees Doug Krisch. “When I look back at the Kyoto Now! images from twenty years ago, it fills my heart with such joy. It all began with a handful of students who were very interested in pushing Cornell to be an environmental leader,” he says.