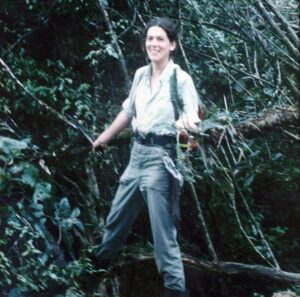

When Sandra Knapp PhD ’86 started her undergraduate career at Pomona College in Claremont, California, she was set on taking a course in marine science. Having grown up in the desert in rural New Mexico, the ocean held great allure for Sandy. But when she was not able to get in because the course was full, she chose field botany instead. As part of her field botany fieldwork, she and her classmates headed into the desert with microscopes, to take a closer look at plants.

“This was it!” she says. She recalls being filled with wonder as she discovered and observed different plants. This sense of wonder has stuck with her over the course of nearly five decades, leading Sandy to explore ecosystems around the globe and describe more than 100 new species of plants. In April, Sandy received the 2022 David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration from the National Tropical Botanical Garden, in recognition of her remarkable career in plant discovery and conservation.

Sandy says she can recall many of the plants she’s seen and the places she’s been in her mind’s eye. “I remember most plants I’ve ever collected like they were my friends,” she says. What she loves about her work is the opportunity to see something new. As a scientist, Sandy gets to experience this on a daily basis. “The best part of my work is also the best part of life—finding something you hadn’t noticed before,” she says.

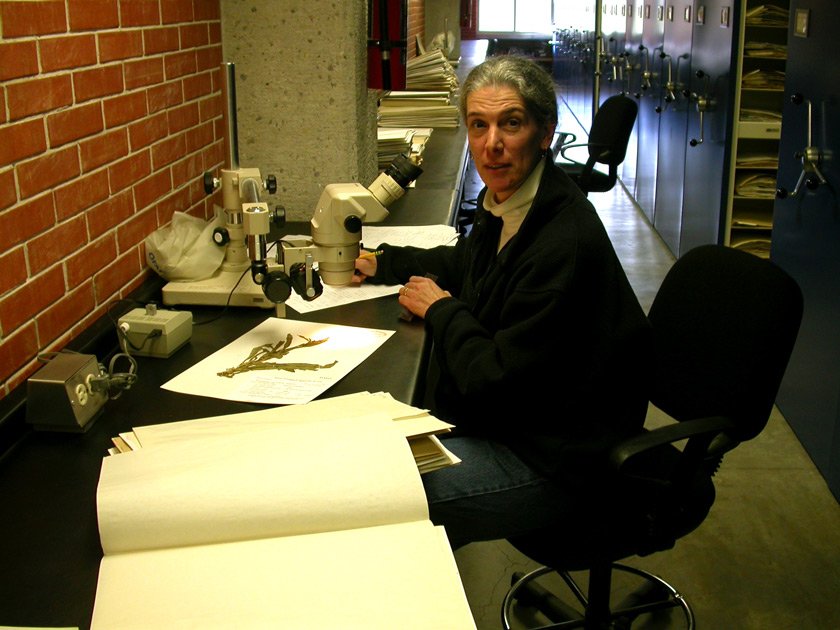

As a tropical botanist and researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, part of Sandy’s job is to share her love for the natural world with others. The mission of the museum, which averaged 5.5M visitors annually before the pandemic, is to create advocates for the planet. For Sandy, this starts with fostering a personal connection to nature.

“Through the whole of the pandemic, many of us were stuck in our backyards looking at our little patch of garden,” Sandy says. “In my yard, I discovered what hairy-footed flower bees look like—they’re very cute.” Sandy sees this as a silver lining, because people became more connected to nature. “Working in an institution like I do makes me uniquely positioned to keep that connection alive,” she says.

Sandy offers this simple invitation in honor of Earth Day. She suggests going outside and being in nature for a minute or two—without talking—to see what you see. “Earth is utterly amazing, whether you’re in a small garden or a tropical rainforest. Think about all the other things we share the Earth with and drink in nature,” she says, adding, “This will help you feel better.”

Naming the unnamed

Sandy recalls spending her most of her childhood outdoors, exploring the desert around her home in Los Alamos. She said that she was always aware that the climate was changing, and that this awareness is part of her psyche. She remembers droughts that brought pine beetles, and torrential rains that washed away hillsides. She also recalls the sense of loss she felt when she traveled through clear-cut forests in Oregon on visits to her grandparents.

“Growing up in NM, you’re surrounded Anasazi ruins. They were a culture that disappeared—possibly due to overexploitation of resources,” she explains. For her undergraduate thesis, Sandy studied a cactus, the cane cholla. This plant is closely related to another cholla that was used by the Anasazi in initiation rituals.

Sandy is fascinated by difference: why plants split up into new species, how these species are unique physiologically, and how these adaptations make the new species better able to survive. She says that her desire to connect these three fields—taxonomy (the classification of plants), plant physiology, and plant ecology—led her to Cornell, to study under Mike Whalen. Whalen was a new professor, and Sandy was his first doctoral student.

“Mike was an amazing person,” she says. “He was only about 30 years old, and he was more like a friend than a professor. He really thought about things, it was inspirational.”

While at Cornell, Sandy took a nine-week course in tropical botany in Costa Rica, organized by the Organization for Tropical Studies—a consortium of about 50 universities including Cornell. This experience was life changing for Sandy, redirecting her focus to the tropics. “No one knew anything about the plants in the forest there, and most of them didn’t have names. I thought, ‘Man, this is great!’”

Following her passionflower

Sandy took a year off of her doctoral studies to do fieldwork in Panama for the Missouri Botanical Garden. She was given a place to live, a truck, and the job of collecting plants for further study. “I drove all over Panama learning all about tropical plants and diversity. I learned to speak Spanish and make lots of friends,” she says.

She recalls one experience in Panama, traveling upriver, when she spotted a passionflower blossom floating nearby. She followed the blossom upstream until she spotted the passionflower plant, high in a tree. She and her friend landed on the bank and climbed into the upper boughs to collect the plant. The branch fell into the river, where Sandy prepared multiple samples for identification and study. It turned out to be a new species, which made the long journey back down the river—in the dark—worthwhile.

Since then, Sandy has traversed tropical landscapes around the world, discovering, studying, and identifying new and unusual plants. She says that the concept of a species is actually nothing more than an opinion about variation. “I look at relationships between things,” she says. “Every single decision I make is about weighing similarities and differences.” For example, she says that a being from another planet might regard all humans as one species, or they might group humans into many different species—depending on their categories.

Sandy says she has recently been pondering why the leaves of a particular plant in New Guinea are sometimes broad and sometimes narrow. She hasn’t been able to find a reason for this difference, and so she considers both leaf shapes as variations within a single species. “You could spend your whole life figuring out why something is the way it is,” she says.

Taking a personal approach

While Sandy does not routinely work in the public policy realm, she believes that scientists have an important role to play in framing conversations in a way that is objective and thoughtful. “In the cacophony of things happening in the world, it’s really difficult to have a voice that’s heard,” she says.

She says she makes a point of talking to people, taking time to listen to their perspectives and respectfully sharing hers. Sandy practices this approach when talking to school kids, working with her own students, and even as a guest at dinner parties.

“It’s important to take a step back and see things through another’s eyes. It takes time to change your mind, and you need time to think about alternative ideas. This goes both ways,” she says.

“Have a conversation, and admit that you could be wrong. Science constantly evolves, and it’s always changing.”

Sandy notes that the Portuguese word for exploration, exploração, also means exploitation. “We need to think about the idea of collaboration, as opposed to the old version of exploration—which was really a form of exploitation,” she says. “We used to bring plants and other things we found back for us, rather than leaving where we found them for the benefit of people there.”

Protecting biodiversity

Change is a constant of life on Earth, Sandy says, but what’s different now is the scale and tempo of change we are experiencing. She compares humans to an invasive weed: “We’ve driven to extinction every other species in our genus, and the changes we’ve made mean there’s no longer enough space for other living things,” she says.

Sandy recently attended COP26 in Glasgow, and she says she came home feeling hopeful. She notes that it’s a painstaking process for representatives from diverse countries to find language they agree on. She was heartened by the fact that the Glasgow Climate Pact includes language to protect the planet’s biodiversity, for the first time.

She understands that when confronted with the “planetary emergency” posed by climate change, people can feel powerless to take meaningful action. Sandy believes, however, that every action is meaningful.

“It’s all about tradeoffs,” she says. “For example, electric cars run on batteries made from minerals mined from the earth. These minerals are non-replaceable, just like fossil fuels. So, maybe, we don’t use cars so much. Every little thing you do—leaving part of your garden wild to attract pollinators, eating all the food in your refrigerator and not throwing it away, limiting your use of plastic—all of these tiny actions accumulate to make a difference,” she adds.

Watch this Instagram Live conversation between Sandra Knapp and Kenyan climate activist Elizabeth Wathuti.

View this post on Instagram