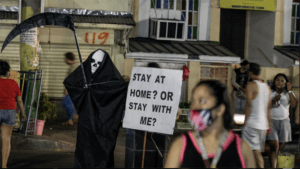

As the coronavirus pandemic unfolded this past spring, students in Janis Whitlock’s graduate seminar on translational research found themselves in a unique position – being able to participate in a widespread journaling project to record their hopes, fears, and routines, chronicling COVID-19’s effects on their daily lives and relationships. It is a project that is both intimately personal and also cast on a global scale.

From around the world, contributors have shared reflections on life during the pandemic and this tumultuous year through “Telling our Stories: in the Age of COVID-19 (… and More),” created by Whitlock, a research scientist and associate director at the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research in the College of Human Ecology.

In March, recognizing that a historic moment was unfolding, Whitlock and lab coordinator Julia Chapman launched the project as an outlet for people across cultures to share experiences about how the coronavirus was affecting them. In just the first two weeks, nearly 260 people from more than 20 countries signed up, recording their hopes, fears, and daily routines in written, voice or video journal entries.

“It has become abundantly clear that the profoundly historic nature of this time transcends the pandemic,” Whitlock said. “We are hoping to contribute to knowledge about how this time has changed life at the individual and collective level – the way we cope, the way we understand ourselves and others, and where we are individually and collectively finding hope.”

The answers to these questions, Whitlock said, could give researchers valuable insight into how people weathered a period of massive social and economic disruption, and into the effectiveness of policies responding to the crisis.

The project came together quickly, after efforts to “flatten the curve” of COVID-19 cases prompted Cornell to send most students home early and transition to virtual instruction for the remainder of the spring semester. Forced to revise assignments on the fly for her translational research seminar, Whitlock thought journaling would give her students, some scattered as far away as China and New Zealand, a timely exercise in “autoethnography” – using personal experience to analyze cultural phenomena.

“They’d have this mini-experience of what it is like to live through an absolutely historically relevant moment; I [didn’t] want them to look back without having done that,” she said. “There was resistance at first among some students. Having to get so close to their daily experience of something that felt so hard was aversive. In the end, though, once they had to look back over their entries and make sense of their documented experience, virtually everyone appreciated the opportunity.”

Research has shown journaling can be a cathartic process, Whitlock said; it is used as an intervention in a variety of therapeutic contexts. “In situations like this, it’s pretty ideal,” she said, “because it allows people a space to deposit stresses and worries as well as inspirations and hopes.”

Expanding the project’s reach

Whitlock, whose research focuses on adult and adolescent mental health and well-being, also thought: Why not open the project to the larger world grappling with social distancing and quarantines? Although millions were documenting their experiences on social media, they may be less likely to engage in consistent, thoughtful reflection on those platforms, she said.

Participation in the expanded project increased steadily, and got an additional boost in early August when the magazine The Atlantic ran a feature, “Dear Diary: This Is My Life in Quarantine,” about journal-keeping during the pandemic that covered Whitlock’s efforts. The project, which is ongoing, now includes more than 719 participants from more than three dozen countries.

“Telling our Stories” is open to anyone as a journaling space, and only those providing consent will be included in any research analysis. Participants submit demographic information and log how they are feeling. They answer questions about the impact of the crisis, their use of social media, and where they have found “silver linings.” Then, daily emails prompt new journal entries along with any updates to one’s health, living or work status, or that of loved ones. Entries can be made as often as desired.

Submissions are private; researchers will not see personal information or include it in publications. Whitlock said the first of those publications will likely be a compilation of stories for participants, highlighting their collective experiences. In that way, she said, the project may prove as much artistic as academic.

Eventually, she expects the stories to present a rich portrait of how people coped over the arc of the pandemic and of the day-to-day impacts of policy interventions—from Cornell’s campus to the international level. Lessons learned could even inform policy in a future pandemic, she said.

Whitlock added that she plans to keep the study open until the pandemic is largely over, and that a follow-up study will likely be built to assess post-COVID-era perceptions.

For more about the project, and for students’ reflections on their participation, read the full article by James Dean and Joe Wilensky in Ezra Magazine.