Early April is a time of year for college acceptances and, this year, for an alumni summit about the first-generation student experience. Attendees dedicated an afternoon at Cornell Tech to panel discussions, networking, and inter-generational conversation about first-generation experiences. The questions they explored included how to encourage first-generation students to apply to college, issues of belonging and succeeding, and the “hidden curriculum” first-generation students encounter. The summit concluded by recognizing two alumnae whose Cornell volunteer work supports Cornell’s diversity in its broadest sense.

Becoming first generation

“When I first arrived on campus, it felt foreign,” said Katrina James ’96, trustee and vice-chair of Cornell Mosaic, in opening comments to the summit. “It was a little bit embarrassing that my parents did not go to college and I felt like I was the only one. But ‘first-gen’ wasn’t a term then, wasn’t a thing then.”

While many alumni will say that being a first-generation student was neither noted nor talked about when they were in college, conversations during the afternoon revealed just how deep the commonality of a first-generation experience is within the Cornell alumni population. With more joining the ranks of first-generation alumni in the years to come, first-generation is a widening audience. Cornell’s incoming class of 2022 comprises 13.7 percent first-generation students.

“This is a new frontier, new cohort of alumni who are part of Diversity Alumni Programs,” said Matt Carcella, Cornell’s director of Diversity Alumni Programs and organizer of the summit. “People think of diversity in many ways; this is an expanded notion.”

First-generation outreach: doing it well

In their panel Community Based Organizations and the First-Gen Pipeline to Cornell, Dan Blednick, director of college guidance, The TEAK Fellowship; Shari Fallis, director of college guidance, Prep for Prep; and Emil Kim, director of programs, SEO Scholars discussed how Cornell and other universities partner with their non-profit organizations to create a pipeline for first-generation students to apply.

The efforts Cornell and other institutions can make to set the scene for first-generation student success may seem like little things but can have a big impact. Examples include providing open dining hours for students who are not able to go home for breaks, having an office to meet with staff that is not in an obscure corner of campus, and locating a center where students can meet people who look like them and do simple, helpful things like use a printer.

According to Kim, a pre-college visiting experience such as Cornell’s—even if students do not apply to Cornell—helps students more strategically construct their college application lists. Said Blednick, “Given its size, it’s surprising how high-touch Cornell is. Cornell is doing it well. This gathering is a testament to that.”

Student viewpoints

When Jessica Velesaca ’22 heard her housemate discussing with her father various course options suitable for premed, it struck her how easy it was for a parent with college experience to answer important college questions, even from afar. Velesaca, an American Studies major in the College of Arts & Sciences, has parents who did not attend college. “Not knowing much about the US college system, it is difficult to explain to my mother what an ‘American Studies’ major is,” said Velesaca. Practical know-how to navigate some essential college topics or questions is part of the “hidden curriculum” that first-generation students may be missing. And the nature of the hidden curriculum is that the students don’t know that they don’t know.

Michelle Duong, a PhD Candidate in the Department of Food Science, recounted that she rarely asked questions of her professors and fellow students in her undergraduate years at Vassar. Because of her upbringing in Vietnam, Duong was taught to rarely question authority figures. Today, Duong feels confident freely asking questions, including of the alumni network, to learn about career opportunities in her food-safety focus. She remarked to the summit assembly, “Alumni, if students work up the courage to reach out to you, please lend them a helping hand!”

Game changers

In a panel on emerging issues, Jimmy Suarez ’09, senior assistant director for diversity initiatives at NYU, spoke about the many ways in which colleges are improving the pipeline for first-generation students. Some of these are simple yet effective, such as making sure campus tours use language about first-generation students. Applicants are caught up with thinking they need to go to college and they need to go to a good college, but forget that they need to fit at their chosen college. Seeing students like them or hearing about first-generation support on the tour can help.

Shakima Clency, Cornell’s associate dean of students for first-generation and low-income students, added that institutions need to identify barriers to success and do the hard work of examining what might go into removing these sometimes policy-based barriers. She also notes that using institutional data can inform actions. Survey data can tell us if students say that they took advantage of the offerings that exist for them.

When asked what would be a game changer for first-generation students, William “Woodg” Horning MPS ’10, Cornell’s senior associate director for the Office of Academic Diversity Initiatives said, “Opportunities for students to have internships in the summer where students don’t have to worry, ‘do I have the money to come back in the fall?’”

Clency would like to see comprehensive programming for direct faculty and mentor interactions, including undergraduate research, that help identify pathways to experiences. Suarez suggested creating ambassadors among the elder first-gen students to guide first-year, first-gen students in aspects of the hidden curriculum.

Intersectionality and recognition

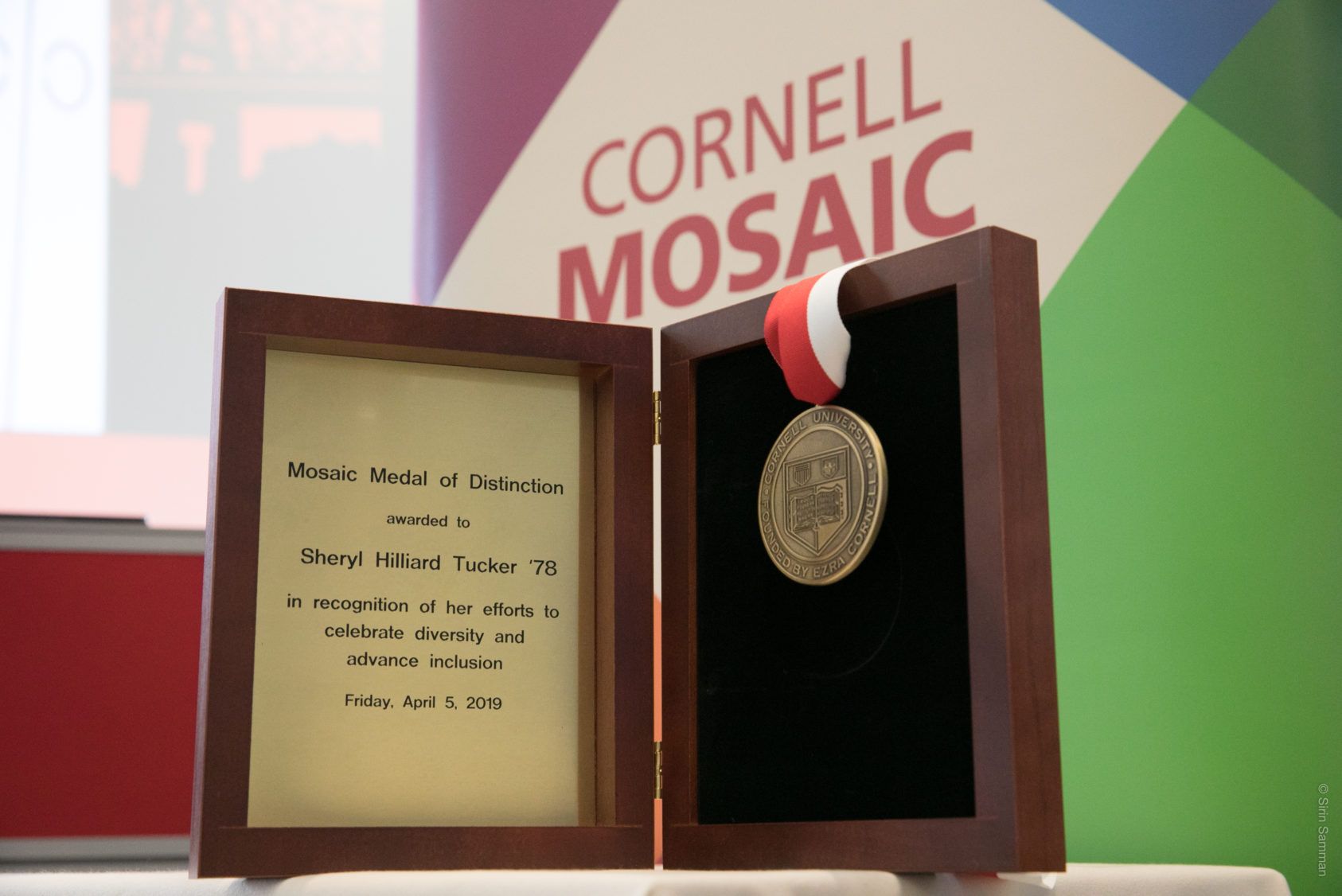

Throughout the summit there was a common refrain from speakers who said, “I was first-generation, too.” The two Mosaic Medal of Distinction winners, Liz Moore ’75 and Sheryl Tucker ’78, followed suit.

“Diversity is what Cornell stands for,” Tucker said, noting that the day was about bringing together under a banner of first-generation some whose voices may not otherwise have been heard.

Moore recounted her family driving her upstate to Cornell. Her mother, originally from Barbados, said, “Elizabeth, that’s a cow. Are you sure you want to go to this school?” Moore went on to express the intersectionality evident in the day’s summit and important to the founders of Mosaic.

The Mosaic Medal of Distinction recognizes alumni, faulty, and administrators for their commendable impact or leadership in creating opportunities and access for diverse communities within the academy, industry, public service, and the professions.

“We are delighted to honor these two alumnae who have helped us open up the diversity conversation,” said Carcella.