Steve Jackson, Cornell’s vice provost for academic innovation, has a big job. For the past year, he’s been working to ensure that teaching in university classrooms, labs, studios, and field sites is aligned with what the latest research tells us about how people learn best. And, that teaching at Cornell carries forward the core values of the institution, while keeping pace with rapidly evolving technologies like generative AI (artificial intelligence), AR (augmented reality), and VR (virtual reality).

“Piece of cake, right?” Steve says.

As a professor in information science and science and technology studies, Steve’s own research is in technology ethics, law and policy, including what he describes as the “planetary dimensions and consequences of computing.” These include energy and water consumption, sourcing and extraction, and technology waste and repair. This perspective makes him well positioned to appreciate both sides of a double-edged sword: the immense promise of technology when deployed judiciously, or, conversely, the darker flip side (in which technology disrupts, in a bad way, the teaching environment and undermines important learning processes and goals).

These mixed challenges and opportunities bring us back to the core proposition of learning itself. As Steve describes:

“We are living in a world of change,” Steve says. “Our students’ ability to thrive in the future is not going to be so much about some piece of information or knowledge that I transmit to them now, in this classroom. It’s going to be about a set of habits, skills, and ways of thinking that will allow them to continue to learn in the future. And to respond in thoughtful, effective, and creative ways to situations in the world as it changes around them.”

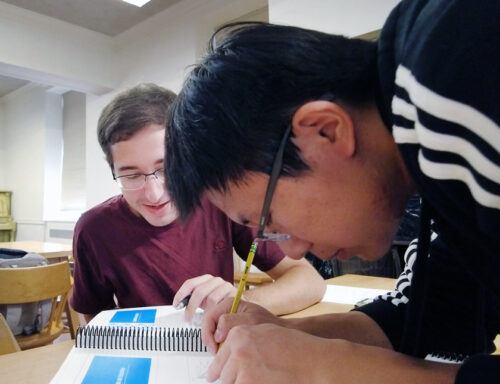

The relationship between teacher and student is elemental.

As vice provost charged with overseeing Cornell’s Center for Teaching Innovation (CTI), Steve continues to regard his title as ‘teacher’ as his highest, most aspirational role. For him, the relationship between teachers and students is the “elemental relation” that sits at the heart of Cornell.

In Steve’s eyes, to be a teacher requires:

- generosity to meet each learner where they are,

- curiosity to learn new and different perspectives, and

- respect for and tolerance of civil discourse—something which he believes is fundamental to democracy and central to the university’s contribution to the current moment.

“We are collectively getting really bad at having conversations across difference in this country, and in many other countries,” he notes. “If we can train our students to have conversations with people who think differently than them, then we have done something to train citizens for democracy, moving forward. That is part of our promise to the wider world—to be a place where tough but important conversations across difference are had.”

Steve has been reflecting on the profession of teaching for most of his life. His father was a K-12 teacher in the blue-collar community in northern Ontario where Steve grew up. He still recalls helping his dad pack up various balls and jump ropes in preparation for the new school year.

Steve came to his current position through a roundabout path. From an undergraduate degree in the humanities, he moved to graduate work in political economy, and eventually communication and science studies—with stints as a worker, teacher, and researcher in Indonesia, Malaysia, and South Korea along the way. As an undergrad studying English and creative writing at Concordia University in Montreal, he was inspired by the collaborative learning model in his writing workshops.

“Everyone comes into a creative writing class from a background, a perspective, and a set of experiences,” he observes. “I really admired how some of my professors were able to engage with different learners across the range of backgrounds they encountered. They showed me a model of academic engagement that was serious and demanding, but also very caring, supportive, and open to meeting students where they were at.”

“Active learning methods help students better understand the material and go beyond learning just to learn it. There’s application, and collaboration. and true interest.” —Deniz Sinar ’23

Throughout his career, Steve has held on to this vision of what happened in his undergrad writing workshops. To him, teaching is a collaborative process where individual perspectives are valued, dialogue across difference is encouraged, and deep engagement among students and between students and faculty happens on a regular basis.

There’s no secret to how we learn.

Steve contrasts the traditional ‘banking model’ of education (a term coined by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire), in which professors transfer knowledge to their mostly passive students, with a more engaged and active model of learning. In active learning, students interact with the material, with each other, and with their teacher to learn from one another. This is a relational system in which everyone benefits and learns.

Cornell has been integrating active learning into the curriculum across disciplines for the past decade. The most recent count showed that more than 10,000 students participated in active learning on campus in the past year. The Active Learning Initiative (ALI) works with faculty in different departments to ‘active-ate’ their classrooms, based on what the research tells us about how people learn.

Steve sums up these findings. In a nutshell, most of us are not good at sitting and passively listening to long lectures. We need to stop, reflect on the material, respond to a question, move around, problem solve, discuss, hear other perspectives, and give ourselves the time and space to process the material.

At first, Steve explains, some faculty members were worried that active learning techniques would reduce the volume of material they were able to present to their students. But as Cornell faculty began to deploy these strategies in their classes, they realized there were big wins—both objectively in student performance measures, and subjectively in student engagement with their classmates and the material.

“Active learning is intended as an antidote or alternative to the model of lecturing where the Charlie Brown teacher voice talks at you non-stop for 45 minutes, ‘Blah, blah, blah,’” Steve explains. “But what happens when I try to recreate my little 12-person writing class in a room of 300 or 400 students? Active learning offers strategies to build a relationship between teacher and student in that context, so that I can reach all of my learners.”

While most of the ALI emphasis thus far has been targeted toward larger lectures, Steve notes that roughly half of Cornell’s 2,500+ courses each semester are small classes, with 20 students or less. Steve is excited at the prospect of developing programs to support learning and innovative teaching in these contexts, too.

The CTI team is currently working with stellar faculty across campus to create a series of events for various learning settings. For example, ‘The Art of the Studio’ will learn from expert insights and outstanding practitioners on how to activate student learning in studio classes in fields like art, architecture, and planning, while ‘The Art of the Lab’ will do something similar for lab classes in science and engineering fields. The goal is to share the insights and inspiration of great teaching across the university, so that faculty in sometimes very different fields can learn from and adapt new practices to their own teaching environment.

“It was clear from the first moment of teaching that it was infinitely better. I remember the classroom coming alive with students talking. It was just delightful!” —Julia Thom-Levy, professor, physics

Steve says that CTI is nationally recognized for its outstanding work to support and strengthen pedagogy at Cornell. From the center’s founding in 2017, it combined two previously separate initiatives: a center for teaching excellence focused on improving the practice of teaching, and an educational technologies unit that was focused on integrating new technologies into the curriculum. This brought the two mindsets together in the new Center for Teaching Innovation.

“Now, these things are integrated and considered together,” Steve remarks. “So, when we think about new tools or new technologies for teaching, it’s no longer about technologists throwing cool tools over a wall. Instead, we have technologists in ongoing embedded conversations with people who have deep training and commitment to teaching.”

We are navigating the generative AI transition.

About half of Cornell’s incoming students report that they are already using generative AI in their work (according to Steve, based on a recent survey administered by the university). The challenge for Cornell faculty is to learn how to use emerging technologies wisely, creatively, and ethically—to enable powerful new ways of synthesizing data, visualizing scenarios, and interrogating results.

CTI’s Creative Technology Lab helps Cornell faculty incorporate virtual and extended reality (VR/XR), digital storytelling, and generative AI into their teaching. CTI has also compiled specific resources for Cornell teachers to help them understand generative AI tools and how best to respond to or deploy them in their classrooms.

For example, students who are learning to conduct an orchestra can strap on a XR headset and see themselves moving in real time from the perspective of the violin section.

In this video clip James Spinazzola, Barbara & Richard T. Silver ’50, MD ’53 Associate Professor of music, demonstrates how XR is a game changer for helping students master the skills of conducting.

Students exploring controversies in American politics can use AI to generate counterarguments to their point of view, to help them understand alternative perspectives and then interrogate these perspectives through class discussion.

Students in landscape architecture classes can use geospatial mapping tools on their iPads or cell phones to inform their understanding of the overlapping layers at a particular study site, including hydrology, geology, cultural history, land use regulations, natural habitats, environmental contaminants, and more.

In this clip Anne Weber, assistant professor of landscape architecture, has her students use tools that are readily available on iPads and iPhones to document and analyze site conditions in Cascadilla Gorge.

Working with Information Science colleague Qian Yang, Steve recently used AI chatbots like ChatGPT with students in his Computing on Earth class, to help them analyze the sustainability plans of companies like Amazon, Google, and Apple. The students did their own critiques of each firm’s sustainability plan. They then asked ChatGPT to critique the reports from the perspective of both a liberal and conservative policymaker. Both the AI-generated critiques were useful in surfacing points that students had not previously considered, and they drove a new round of class discussion and student reflection.

He notes that, despite widespread fears about students using AI to cheat or do their work for them, this is not what the bulk of Cornell students are doing. Students self-report that they use AI to review their class notes and point out gaps where they might have missed something—something which can be helpful for students whose first language is not English (or students with learning differences, etc.).

“Technology will continue to come into our classrooms, in interesting and challenging ways,” Steve observes. “Both of those things are true—both interesting and challenging. Our teachers are finding effective ways of dealing with new technologies like generative AI. In the end, like with prior changes in the classroom environment, creative and thoughtful teachers will prevail,” he adds.

Cornell is a training ground for future faculty.

To prepare the next generation of teachers, CTI offers a series of institutes to grad students, teaching assistants, and post docs. These offerings support students to design and implement best practices in their classrooms. The goal is to prepare grad students for their future teaching-related endeavors, whether within or beyond the classroom.

The institutes offer a menu of course options for teaching assistants—from how to foster inclusive classrooms and engage a diversity of viewpoints, to how to grade fairly, to how to incorporate evidence-based practices about how people learn into their curriculum. These options are voluntary, and, as of the 2023–2024 academic year, nearly 800 individuals participated in CTI’s grad student programming.

Steve envisions these offerings developing into a full-fledged graduate teaching academy on campus, where he hopes to build a pipeline to cultivate the next generation of faculty. These are scholars who embrace teaching as a core part of their identities.

“I can attribute nearly everything I know about teaching today to what I learned through the CTI.” —Lauren Genova, PhD ’20 (currently an assistant professor at the University of Delaware)

“I want us to develop a reputation that, if you hire a PhD from Cornell into a faculty job, you know they will care about teaching,” Steve says. “And that when you hire a Cornell grad in whatever field, you know that this is a serious professional who will engage with undergrads (and colleagues) in a thoughtful, research-informed, and committed way.”

He humbly qualifies this aspiration with the reminder that no one can be a perfect teacher. As he says, “teaching is an infinite art.”