Electric vehicles today are clean, quiet—and relatively inconvenient.

It used to be that you plugged an electric vehicle in overnight and it would go maybe 100 miles, says Jeff Wolfe ’82, President, for the Americas, of Tritium, a company that focuses on electric vehicle chargers.

The process is getting faster: a Tesla can now go over 300 miles after charging for only an hour. “The fastest chargers we’re making are more than three times faster than that,” says Wolfe. “We’re making the very fast chargers that are beginning to replicate a fueling experience.”

Creating that convenient experience drivers are used to—pulling into a station, waiting a few minutes, then getting back on the road—is key to making electric vehicles mainstream, says Wolfe, who founded a solar company in 1998 and has been working on clean energy problems ever since. And so is informing consumers of the benefits and growing convenience of electric vehicles.

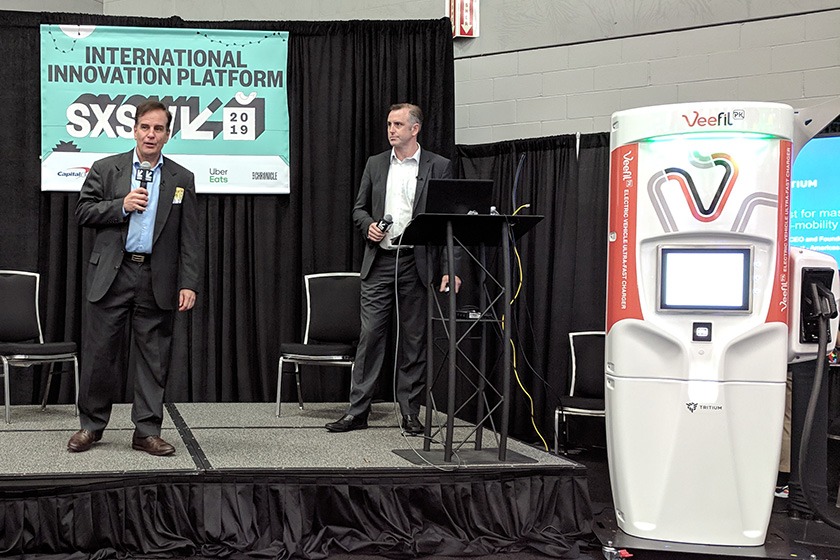

He presented Tritium’s fast chargers and the benefits of mainstreaming electric vehicles at SXSW 2019 in March.

“One of our goals is to charge cars,” he says. “Our other goal is to help create cleaner, healthier cities.”

Electric vehicles will benefit the environment and personal health. All-electric vehicles don’t release carbon dioxide and other health-harming pollutants into the local atmosphere as conventional vehicles do, and therefore contribute less to climate change-accelerating greenhouse gases. An electric vehicle, Wolfe points out, pollutes significantly less than a fossil fuel car due to efficiencies in electric power. Electric vehicles can increasingly be fueled by renewable sources of electricity, including solar and wind, as more clean energy is installed across the country. Electric vehicles are also quieter than conventional vehicles, especially in cities.

“About ten years ago, I was walking in New York City, and I had this vision: Imagine what this will not sound like,” Wolfe says. “Lower ambient noise is a health benefit.”

A critical mass of all-electric vehicles will contribute to an improved overall electrical grid. Currently, electric vehicles are a difficult load on the grid, but technology is coming out, Wolfe says, that will allow electric cars to both draw from and contribute to the grid, making the whole system more resilient and more open to renewable resources than it is now.

Wolfe learned to think in systems at Cornell, while studying systems control feedback in a mechanical engineering course.

“I started looking at all things in the world as system control feedback: this conversation, personal relationships, the electrical grid, or politics,” he says. “That was a foundational class that has shaped my thinking greatly.”

A second Cornell class that comes up in his work all the time: public speaking. In addition to working with others in his company and industry to solve the engineering problems associated with building fast chargers and integrating electric vehicles into traffic, Wolfe spends much of his professional time and energy sharing this developing story.