Benjamin Z. Houlton, Ronald P. Lynch Dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) at Cornell, is on a mission to use science to find solutions to climate change. And, like David in the epic battle against Goliath, Houlton is using rocks.

In a nutshell, Houlton’s work involves capturing carbon from the sky and putting it into the soil, where it can remain locked up for thousands of years or longer. To do this, researchers are using recycled rock dust to enrich farm and rangeland soils, in order to accelerate natural weathering processes by which soils capture atmospheric carbon.

Earth provides its own slow, but proven method of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through the process of rock weathering. This process maintains the volume of atmospheric carbon within the relatively narrow bandwidth that sustains life on our planet. Too much carbon accelerates the greenhouse effect, causing rising temperatures and a host of other challenges to global security, food production, economic growth, infrastructure, and human and ecosystem health.

On February 22, Houlton presented early results from his research on enhanced weathering as a carbon capture strategy to Cornell students in 2021 Perspectives on the Climate Change Challenge Seminar Series. According to Houlton, this strategy has the potential to solve multiple challenges at once. “It’s a low-tech solution with tremendous capacity to capture carbon on our planet,” he said, “but the science still needs to advance for us to gain confidence.”

How does it work?

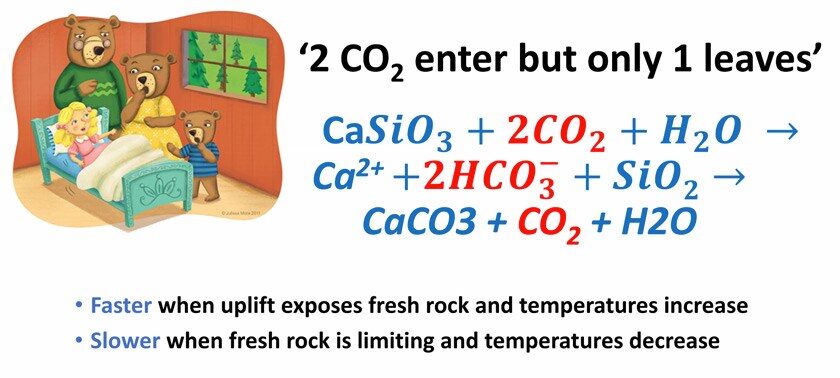

Houlton began by explaining the critical role that rock weathering plays in maintaining a stable climate. For every two carbon dioxide molecules that enter the soil, one of these molecules is broken down through the process of weathering and is released into the ocean as calcium carbonate. The other CO2 molecule is released back into the atmosphere. “Two CO2 molecules enter, but only one leaves the soil,” Houlton explained.

The weathering process happens faster when temperatures rise, and slower when temperatures drop, in what scientists call a negative feedback effect. The result is that Earth enjoys a stable climate, “instead of runaway carbon release like on Venus,” Houlton said. He explained that our planet’s current concentration of greenhouse gases allows us to maintain a “Goldilocks” temperature, which is “just right” to sustain life. “If Earth didn’t have its current greenhouse gases,” Houlton said, “we would be as cold as Mars.”

Without strategies to amplify the rate of carbon capture, Houlton said that we cannot mitigate the negative impacts of climate change.

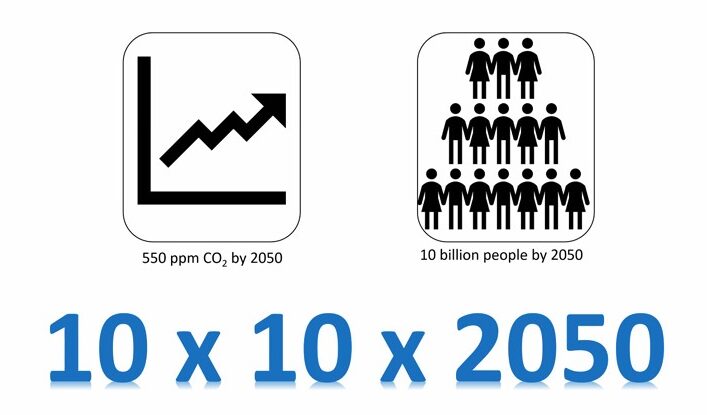

“About 0.5 billion tons of CO2 are removed naturally by rocks each year,” he said, “which in no way can stop the current CO2 influx [into the atmosphere] from people.” Without carbon capture, Houlton said we can expect a carbon concentration of 550 ppm by 2050, a level that has not been seen on Earth for more than 20 million years.

Houlton’s research looks at how best to speed up the weathering process. One way to do this is by adding volcanic rock dust to soil. This rock dust speeds up the chemical reactions that break down rocks—thus increasing the rate at which carbon is captured into the soil.

In order to meet the targets established by the Paris Climate Agreement, Houlton said we need to capture 10 billion tons of carbon by the year 2050—while still feeding an estimated population of 10 billion people.

But does it work?

Houlton explained that researchers first began testing enhanced weathering in the early 2000s, by testing various kinds of rocks in lab settings.

“These lab results show huge potential but lacked a real-world test,” Houlton said. “Our median estimate is that applying crushed volcanic rock to agricultural soils around the world could remove 2.8 billion tons of carbon over a five-year period.”

The next step was to test the technique in the field. For the past year, Houlton has partnered with a coalition of research, government, tribal, and private sector partners through the Working Lands Innovation Center in California. The project has worked with farmers and ranchers throughout California to deploy soil amendments and measure the results.

“I am a firm believer that we need to have an inclusive approach that incorporates all of the stakeholders,” he said. According to Houlton, this approach quickly underscores what kinds of benefits farmers and ranchers need to embrace the strategy, as well as what the barriers to adoption might be.

Cornell CALS is now involved too, Houlton said, expanding the project to a bi-state consortium between California and New York.

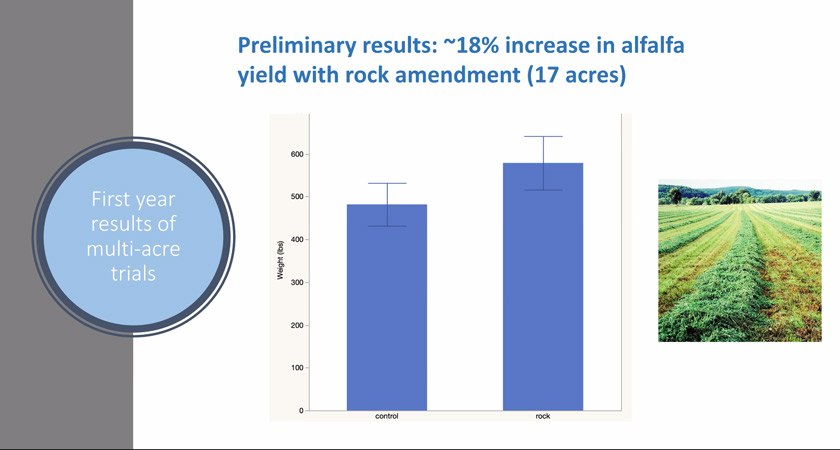

Field testing has been ongoing for the past year, and early findings are positive. Iris Holzer, a PhD student at UC Davis, has seen a doubling of the rate of carbon capture in soils with rock amendments, compared to soils without them.

“The bottom line is that these are incredibly exciting results,” Houlton said. “This is the first time, to our knowledge, that we have large-scale, in-situ results of enhanced weathering,” he added.

Why is this approach a win-win-win?

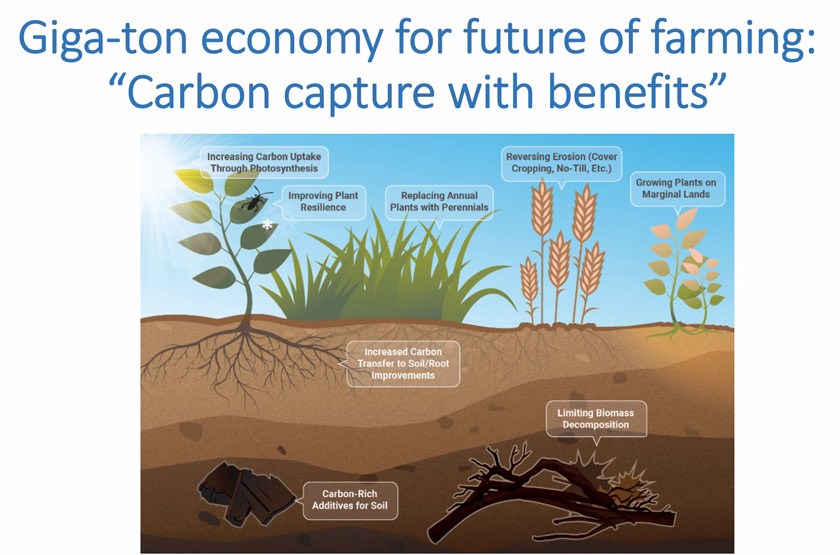

Houlton describes the enhanced weathering technique as “carbon capture with benefits”—referring to several market-based, collateral benefits that make the approach even more appealing.

The first co-benefit is that “we don’t need a lot of new equipment, just a basic spreader to spread the rock dust,” he said. Researchers have been working side-by-side with California farmers and ranchers to show them how simple the process is and to measure the results. So far, the cost ranges between $60 to $300 per ton of carbon capture, “which compares favorably to other carbon capture technologies,” Houlton said.

Another co-benefit of farming with rock dust is that the dust releases nutrients that are vital to plant growth, such as phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, and calcium. Preliminary results show increased crop yields in alfalfa and corn, in plots with the added soil amendments versus plots without them. “There is evidence that soil amendments can help ameliorate mineral nutrient loss as a result of increased carbon in the atmosphere,” Houlton said, “and help fortify our food,” he added.

Another potential co-benefit is that the amendments can help rebuild eroding soils. “The silica in the rock dust helps to strengthen plant stems and reduce erosion,” Houlton explained. The amendments also enable the soil to utilize fertilizers more efficiently. “We need to keep testing to see if these co-benefits reveal themselves,” he said, “and to identify the right mix.”

So far, the rock dust used has been recycled from mining and manufacturing operations. “We’re doing a lot of lifecycle research to minimize upstream impacts,” Houlton said. “Estimates show that there is a huge amount of slag, kiln, and demolition waste from industries in China, the U.S., and the rest of world that can be repurposed” as a source of rock dust, Houlton said.

The takeaway is that enhanced weathering has the potential to scale quickly, requires low capital investment costs, and provides a pathway to securely lock up carbon for thousands of years—with valuable co-benefits to enrich both the productivity of soil and our global food supply.

“We still need a lot more R&D to establish that this will be an effective solution,” Houlton said. “I believe soil can be part of the solution set. It will not save us, but it can help to put us on path to negative emissions,” he added.