Ingrid Zabel ’87 is Climate Change Education Manager for the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), a small but mighty presence situated across Cayuga Lake from Cornell. The Ithaca-based institution is nationally recognized for its top-notch education resources about the history of life on Earth.

Zabel’s job is to make climate change science more accessible to the public, via exhibits at the Museum of the Earth and the Cayuga Nature Center, teacher resources, and education programs for youth and adults. She also curates two online portals for climate change resources in the Northeast: the New York Climate Change Science Clearinghouse and resilientMA.

In 2017, Zabel and her colleagues at PRI released The Teacher-Friendly Guide™ to Climate Change (TFGCC). Over the past two years, the book has been distributed to more than 50,000 teachers in 44 states nationwide, including every public high school science teacher in New York City and in twelve states.

The National Center for Science Education recently awarded PRI the 2019 Friend of the Planet Award. Ann Reid, the Executive Director of the National Center for Science Education, described the book as “the single best available resource for teachers on climate change.”

From Ithaca to Greenland

Ingrid Hoffmann Zabel grew up in Ithaca, and her father, Roald Hoffmann, is Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters and a Professor Emeritus in the chemistry department. She attended Cornell as an undergraduate, graduating in 1987 with a degree in physics. Her brother, Hillel Hoffmann ’85, is also a Cornellian.

After Cornell, Zabel pursued a PhD in physics at Ohio State University (OSU), where she served as a postdoctoral research associate at OSU’s Byrd Polar Research Center. Zabel travelled to Greenland, where her team conducted radar studies of the ice sheet in order to provide ground-truth data for satellite-mounted radar observations.

According to Zabel, Greenland’s ice sheet is important because it locks up much of Earth’s fresh water. “In the early 1990s, scientists knew that Earth was warming and wanted to know what was going to happen to the Greenland ice sheet. Would it shrink due to excess melting or would it grow from more snowfall?”

Warming temperatures melt the sea ice, causing more open water to be exposed in the Arctic Ocean. Three decades ago, scientists thought that the open water would result in more evaporation and thus more water vapor falling as snow on Greenland. It wasn’t clear which effect would be dominant: ice sheet growth from increased snowfall or loss of ice from melting as Earth’s climate warmed.

“Now we know!” she says. “The ice sheet is definitely shrinking as a result of warming temperatures.”

Back to Ithaca

After earning her PhD from OSU, Zabel worked at MIT’s Lincoln Lab on a radar project in Hawaii. Her next position—as mother to two children—was unpaid, and brought her home to Ithaca to be closer to her family.

She first joined PRI to assist with fundraising. Two years later, she moved into the education department.

Over the past decade, PRI has published a series of Teacher-Friendly GuidesTM, intended to provide rich content and curriculum ideas for Earth science teachers. Previous titles include the Teacher-Friendly Guide™ to the Evolution of Maize and the regional series of Teacher-Friendly Guides™ to Geology.

The development of each of the guides was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation. Most recently, the TFGCC was funded by a National Science Foundation grant to Cornell climate scientist Natalie Mahowald.

“Natalie is a lead author on the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment reports,” says Zabel. “Not only was TFGCC a logical and important addition to the teacher-friendly series, but it was also a great way to extend Natalie’s science and the science of climate change to a larger audience,” she says.

“It’s wonderful to have a high-quality resource for teachers across the country to better inform their students about the challenges and opportunities of climate change,” says Mahowald, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell.

A breadth of expertise

“I think one of the strengths of The Teacher-Friendly Guide™ to Climate Change is its breadth. This breadth reflects the strengths of PRI,” Zabel says. “Each of my colleagues brings different strengths and background interests, and they all came together in one book.”

The TFGCC team includes Zabel and six esteemed Cornell colleagues:

- Warren Allmon, Hunter R. Rawlings III Professor of Paleontology, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, and Director of the Paleontological Research Institution

- Louis Derry, Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, contributing author and reviewer for TFGCC, Director Critical Zone Observatory National Office, reviewer of teacher professional development climate activities for PRI

- Don Haas, current Director of Teacher Programs, Paleontological Research Institution, and former Visiting Assistant Professor of Science Education

- Natalie Mahowald, Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, and Lead Author IPCC Fifth Assessment Report on Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis

- Alexandra Moore, Senior Education Associate, PRI, retired Director of the Cornell University Sustainability Semester and Visiting Associate Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences

- Robert Ross, Associate Director for Outreach, Paleontological Research Institution, and Adjunct Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences

Other Cornell partners include the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies, which funded TFGCC distribution to NYS teachers through a summer 2018 professional development workshop. The Critical Zone Observatory National Office, formerly based at Cornell, funded instrumentation installed at the Cayuga Nature Center to teach local school children about climate change.

Education with a public purpose

“Since publication of the TFGCC, we have seen study after study reinforce our belief that teachers, students, and parents support teaching and learning climate science,” says Alexandra Moore, a TFGCC contributing author. She points to the Ipsos/NPR poll released on April 22, 2019 (Earth Day), Four In Five Parents Want Schools To Teach About Climate Change, as just one example.

She explains that many teachers don’t have the resources they need to do the job well. “The TFGCC provides teachers with high-quality climate science and helps teachers understand the issue from the perspectives of multiple disciplines,” says Moore.

Zabel believes that one of the strengths of the book is the fact that it encompasses both the science of climate change alongside several chapters devoted to the social science of climate change. “It has a chapter on regional climate change, so that teachers anywhere in the US can find something locally relevant,” says Zabel. “There are three chapters devoted to climate solutions, and I know that the chapter on Frequently-Asked Questions is really useful. Teachers, students—and all of us, really—have lots of questions,” she says.

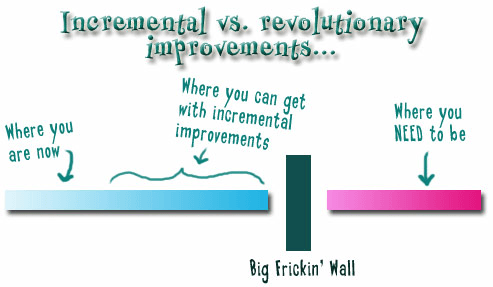

“To understand climate change deeply requires more than just understanding the physical science,” says co-author Don Haas. “The psychology and sociology related to climate change denial and to our difficulty in moving away from the status quo—even when we understand the physical science—are also hugely important.”

“What actually makes people, institutions, and governments change their minds and change their behaviors generally involves far more than just having facts explained. Emotions are in play. Logical fallacies and cognitive biases can easily trick people into believing things that are simply not true. We can address all of these issues more effectively with a deeper understanding of the social sciences,” Haas explains.

The TFGCC provides teachers with strategies for addressing climate skepticism, should it come up in the course of their discussions about climate change. “Most parents do want this content taught,” says Haas. “Teachers need to know that resistance is relatively uncommon and that they have strategies for addressing it, should it arise,” he says.

Zabel is already thinking about what to include in the second edition of the book. “The science is always progressing,” she says. “I’d like to expand the solutions chapters to talk more directly about actions that young people can take. And we are working on developing classroom and outdoor activities to accompany the book, something which we didn’t fully build out in the first edition,” she adds.

A campaign to teach climate science

Back in 2017, just as the TFGCC was going to press, the conservative Heartland Institute announced that it was sending 200,000 copies of its booklet, “Why Scientists Disagree about Global Warming,” to science teachers nationwide.

“The TFGCC authors took on the challenge of responding to Heartland with a crowdfunding campaign to counter climate change denial with actual climate science,” says Moore, leader of the Teach Climate Science outreach effort at PRI. “We need to ensure that teachers and their students have access to the best possible information.”

PRI is currently raising funds to send the The Teacher-Friendly Guide™ to Climate Change to every public high school science teacher in the US—free of charge.

“At a cost of $2.50 per teacher, we are sending digital and print copies of the TFGCC on a school-by-school, state-by-state basis,” says Moore.

The campaign has garnered national attention in Sierra Magazine and on PBS’s Frontline, and has raised more than half of its current $250,000 goal. This is the total needed to put a book in the hands of about half of the country’s 200,000 public high school science teachers.

According to Moore, teachers have responded enthusiastically, citing the book as a “must-have” resource for teaching students about climate change.

“We have thousands of books downloaded from our website, so those individuals had to seek us out to find the resource—presumably on the recommendation of a peer,” says Moore. “And we’ve received a lot of positive feedback from teachers.”

Thomas Adams, principal of Hamburg Middle School in upstate New York, writes, “There is a spirit within the work that leaves the reader hopeful and energized about the possibilities for improving present conditions and future outcomes… The potential good that can come from an energized teacher imparting knowledge and optimism to a cohort is impossible to measure.”

With just over $113,000 to go in the campaign, one thing is certain, says Moore. “We know that teachers can’t use the TFGCC if they don’t have it!”